How a ‘debt-free’ scholarship for California college students became laced with delays, skepticism

Some students haven't received a disbursement for months, among other problems

PHOTO CAPTION: UC Merced during its first day of fall semester in August. UC Merced/Sam Yniguez

By RACHEL LIVINAL

MERCED, Calif. — In September, Tilo Brar was ready to send his daughter off to UCLA.

He bought her a comforter and set up her dorm.

Aside from the nerves of sending his daughter off hundreds of miles away from the Bay Area for the next four years, he was mostly prepared – until about 10 days before the quarter started.

Brar looked at his daughter’s financial aid package only to find it had been converted from fully covered tuition into a bill of over $8,000. His daughter, India, had initially received a loan known as the Parent PLUS, an unsubsidized loan for parents of dependent students.

All of her tuition would be paid and she was ready to begin school. Brar wasn’t expecting India to run into problems.

But when the university received funds through a scholarship known as the Middle Class Scholarship, that’s when Brar noticed issues. His daughter was a recipient for one of the scholarship awards.

According to the California Student Aid Commission, the Middle Class Scholarship is for undergraduate students and those pursuing a teaching credential whose family income and assets add up to $217,000.

It was introduced in 2016 as a “debt-free” way to help middle-class families send their children to any California State University, a bachelor program at a California community college, or a University of California like UCLA.

But, instead, dozens of students have encountered headaches dealing with the process – mostly stemming from unexpected changes to their financial aid.

Some of the problems include students not getting their disbursement for months, or the scholarship amount decreasing before – or after – they get awarded. This is on top of issues that come with receiving other aid.

Brar and his daughter are among those who say they have seen their financial aid suddenly vanish – then reappear. Earlier this fall, the Brars say, the financial aid reappeared less than 72 hours before the first day of class — they say thankfully it hadn’t changed.

What had happened, according to what Brar was told, was that UCLA’s financial aid office had to recalculate his daughter’s financial aid after the campus received the Middle Class Scholarship funds.

Brar said he feared if his daughter hadn’t gotten her money back, her academic achievements would have seemed worthless. They had no backup plan for college.

“I'm just trying to put my kid through school,” Brar said. “She busted her ass and she got into a great university and I'm really happy … I didn't realize ‘hey, you're gonna yank everything.’...the implementation was just horrible,” Brar said.

A big change to the system

Brar wishes the process of receiving a Middle Class Scholarship was more seamless – and he isn’t alone.

Financial aid administrators who spoke to KVPR, too, say offices can often wait a long time to disburse Middle Class Scholarship awards because of unreliable award information from the Student Aid Commission, the state agency responsible for administering financial aid programs. One administrator even said they considered quitting their job because of the problems with an updated version of the scholarship program, despite working in the financial aid office for 15 years.

Although the Middle Class Scholarship has existed since 2016, it didn’t always have the problems it has today.

The scholarship takes into consideration multiple factors: the income a student reports in their FAFSA (Free Application for Federal Student Aid), the cost of tuition for the university the student is enrolled at, and any other financial aid or grant money they may receive.

Shelveen Ratnam, a California Student Aid Commission spokesperson, said the commission is given an appropriation every year that dictates how many scholarships are handed out. The scholarships are decided based on the number of students who are eligible.

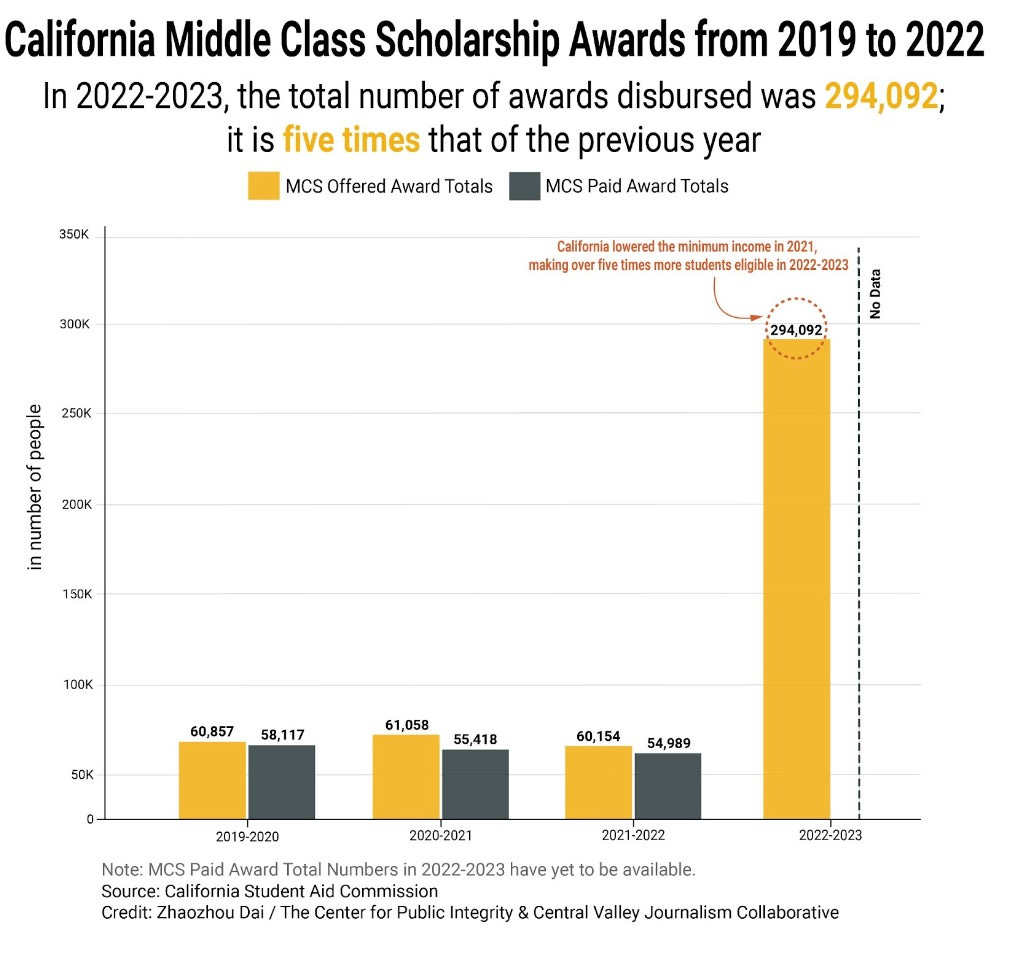

In 2021, California through its budget lowered the minimum income required for recipients of the Middle Class Scholarship. That made over five times more students eligible than before and rebranded the scholarship to “MCS, 2.0."

College financial aid offices scrambled to get the money out to the new larger number of students.

Ratnam said the amount of money can also “fluctuate throughout the school year.” He said financial aid receives a roster of students who are eligible for the award and the amount they are eligible for from the commission.

Responding to concerns from college administrators, Ratnam says he is surprised to hear there is mistrust and confusion, but the Student Aid Commission tries to get feedback on the scholarship’s execution. He says the program is “continually evolving,” and “there has been a short timeline to implement the changes.”

“We continually meet with institutional partners and financial aid administrators to keep them apprised of changes to financial aid programs,” Ratnam added.

Ratnam also said Student Aid Commission staff try to address situations where students see problems with their scholarship awards.

In a response to questions from KVPR, CSU officials said the changes to the Middle Class Scholarship led to “significant modifications to systems at the California Student Aid Commission and the CSU.”

Various problems with the scholarship were outlined last academic year in a 2023-2024 budget analysis, where the California Legislative Analyst’s office made suggestions for improvements.

According to a budget brief, the commission is “exploring legislative changes to simplify program administration.”

Another recommendation to fix the program was to provide ongoing funding for the scholarship instead of one-time funding as it had been designated before. This would remove the uncertainty among students and families. But commission officials said this could come with other challenges due to constraints with the state budget.

“Increasing ongoing [Middle Class Scholarship] funding in 2023‑24 would involve difficult trade‑offs,” according to the budget analysis. “To avoid exacerbating the state’s projected out‑year operating deficits, the legislature would likely need to redirect funds from other ongoing purposes to support any ongoing [Middle Class Scholarship] expansion.”

The changes implemented for the fall included allowing former foster youth to retain the full scholarship and redetermining what is considered “aid” when calculating other sources of financial aid.

Although most hoped this academic year would run smoother than last year, CSU officials said “the data provided by California Student Aid Commission had award errors that they needed to fix before the CSU could begin awarding and disbursing.”

This resulted in the awards coming later this fall than CSU anticipated.

Household income a big factor

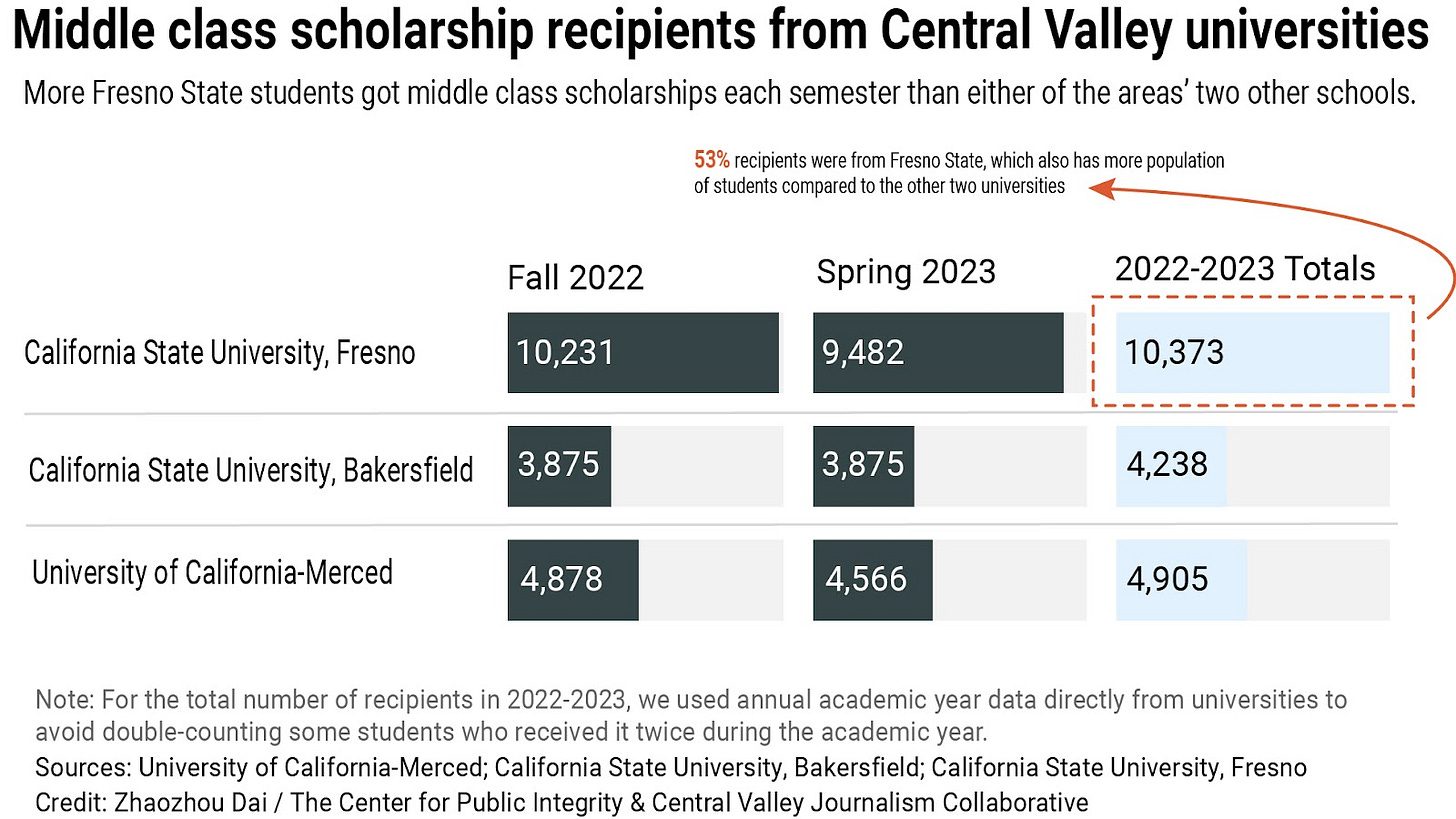

According to data obtained from San Joaquin Valley universities like Fresno State, CSU Bakersfield and UC Merced, 19,516 students received the Middle Class Scholarship last academic year. Out of those, 53% were from Fresno State, which is also more than the student population of the other two universities.

The campuses are set to receive scholarship funds again this year.

AJ Grant is a fourth year student at UC Merced, whose thoughts on the scholarship have varied since receiving it for the first time last academic year. Grant was grateful for the money he received, but at first he said he had a different concern: he didn’t think the scholarship was real.

“I thought it was a scam at first until I found the official UC page on the Middle Class Scholarship.”

Grant received around $5,000 for the last academic year, which helped him pay tuition for a semester abroad. This fall, he got several emails about the scholarship from the Student Aid Commission and from UC Merced.

While the Student Aid Commission informed him he would get about the same amount he did last year, UC Merced lowered that amount to about $3,000. Ultimately, Grant received $2,500 this semester, and expects he’ll receive the same for next semester, but he didn’t understand why his number fluctuated at the time.

“There's this idea that every semester I should be getting more financial aid than the semester before and I see that in my student loans because I'm offered more student loans every year,” Grant said. “So the idea that I was getting less — I wasn't prepared for that.”

Grant’s reliance on the scholarship may differ from most students in the Valley. His father reported around $300,000 in income on his FAFSA for years before, which put Grant above the threshold of $217,000 to qualify for the Middle Class Scholarship.

But the pandemic halved his reported household income, which is why he was eligible for the scholarship.

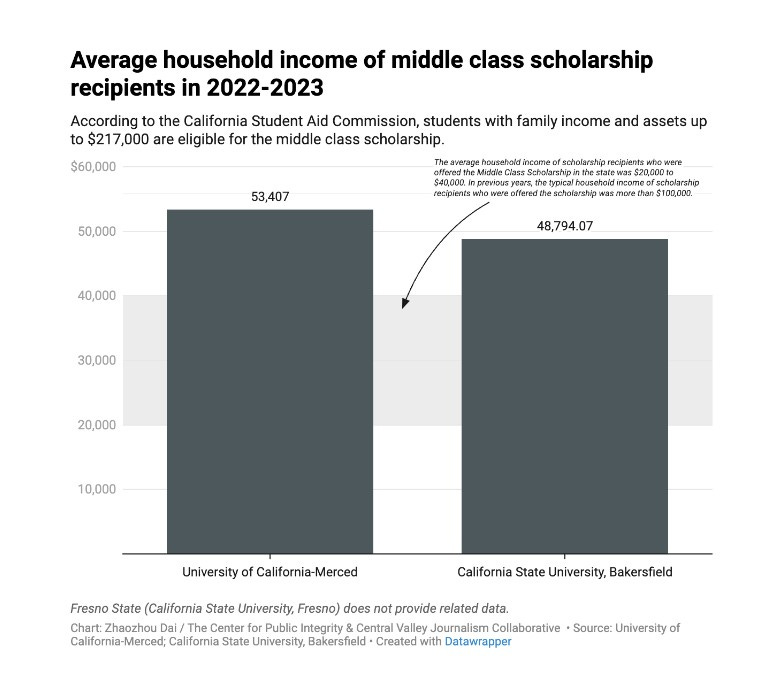

The average household income of the students who received the scholarship at UC Merced and CSU Bakersfield ranged from $40,000 to $55,000 which is similar to the average household income of scholarship recipients who were offered the Middle Class Scholarship in the state: $20,000 to $40,000. In previous years, the typical household income of scholarship recipients who were offered the scholarship was more than $100,000.

Grant’s family income comes in stark contrast to most of the students who attend UC Merced, a university that has over 60% of its undergraduate students labeled as eligible for the Pell Grant, which is a grant given to students with “exceptional financial need.”

Some of those students are Grant’s friends. He said if their scholarship amount decreased from other financial aid or family income, it didn’t make much difference to them.

“I have friends who were expecting to get $1,000 from the [Middle Class Scholarship] and then they are now getting $500,” Grant said. “But that's on top of their $20,000 in other grants…. That's just the fluctuation of financial aid to them.”

Some students report paying money back

According to CSU’s own website, the scholarship amount a student is estimated to get from the Middle Class Scholarship is always “subject to change.”

Because the scholarship is given on a “last-dollar” amount basis, meaning the scholarship amount is determined after everything else is calculated, students can see their estimate but end up getting more or less than what they thought. They can also end up having to pay some of it back.

Nathan Fry got his teaching credential from San Diego State University in the spring, but before he graduated, he was given the Middle Class Scholarship. He said the campus financial aid office sent him multiple emails saying the amount was correct, so he budgeted around the money.

“I had started to put some stuff on credit cards [during the pandemic],” Fry said. “It was a huge relief that I could pay off some debt, put some money towards rent.”

About a month later, he got a bill from the financial aid office saying he owed $1,400, which he said was more than a month’s rent.

Fry received education benefits as a veteran. Even though Veteran Affairs paid off his tuition straight away, the financial aid office calculated his scholarship as if it had not been paid.

When Fry went to the financial aid office at San Diego State, he was given a “University Grant” to try to set off the mistake. That paid for about half of the money he owed.

But, in a couple months, the scholarship recalculated once again due to the grant he got, and the same formula from the fall was used for the spring semester, which raised his fine to about $1,600.

Fry said trying to get rid of the debt became a hassle when it was supposed to be easy.

“It took weeks to get this even figured out and I had to get one of the main guys at the financial office — not like a student worker — [to] go through everything with a fine tooth comb,” Fry said. “How do you expect me to find this if you can't even barely do it?”

Several other students shared similar experiences on social media, and some reported owing more than Fry did, he said. At one point, Fry considered making a small claims file against the university, but he ultimately did not.

Tilo Brar, the parent of the UCLA student, also experienced the fee.

A couple weeks ago, he said financial aid charged him the amount of the Middle Class scholarship his daughter was given because he had appealed the higher income reported on her FAFSA. Brar was laid off this year, and later created a start-up which decreased his family from two incomes to one.

Because the scholarship is meant to help middle-class families, Brar’s lower income meant his daughter would receive less money from the scholarship, resulting in an overpayment from the university.

Brar ended up paying the amount he was charged on his credit card from the overpayment of the scholarship after several more calls to the financial aid office. Brar still isn’t sure if his situation with the Middle Class Scholarship has fully been resolved.

Students thankful for scholarship, but delays persist

Despite the headaches, CSU officials also said they are grateful for the increased aid the scholarship brings to their students. Some students also had positive things to say about the scholarship.

Mikayla Caltrider, a student at San Diego State, had to pay back some of the scholarship she received last year, but she thinks the idea of it is great.

“In theory, it's really nice because you file FAFSA and you automatically qualify and so here's a scholarship that you didn't have to write an essay for or anything like that.”

Grant, the UC Merced student, also thinks it helped him out, even if he is in his final semester.

“It’s too late for me not to take out loans because I didn't know that I was going to be getting this money,” he said, “So I've already taken out the loans. I guess I'll just pay it off a little bit earlier now.”

But still, students, parents, and some university faculty find a stark contrast between the way the scholarship is meant to help, and how it has caused frustration.

PHOTO CAPTION: Tilo Brar helped his daughter, India, move into her dorm for her first semester at UCLA, along with his wife. PHOTO/Tilo Brar

When Jacob Smith started filling out his FAFSA early in the year to attend California State University in East Bay, he didn’t expect to receive a lot. Smith, 25, took a break from school in the midst of the pandemic. Although his income would be reduced once he started school, the financial aid form asked for his 2021 income information.

He had previously lived in Solano County and was about an hour and a half away from campus, so he thought he’d have to commute, even if that wasn’t what he wanted.

“The previous year when I had full aid, I lived [on campus] and I got a lot out of it,” Smith said. “[I] did a lot of networking, had people to work with on my projects and it was just a much better environment for actually learning the material.”

This past summer, Smith checked his expected financial aid package, and found the Middle Class Scholarship along with his options of federally-based loans. The package said he was getting $3,413 in financial aid for the fall – just enough to cover a semester with on-campus housing.

“That's enough that I can kind of stretch to actually afford living on campus, which is where I am now,” Smith recalled thinking.

He signed a lease for an apartment this August, and waited for his disbursement. But the money still hasn’t arrived. CSU officials told KVPR campuses were starting to award the Middle Class Scholarship this year to students in October. But CSU East Bay, where Smith is a student, recently announced students would not receive their scholarships until December.

For a lot of students, problems with delayed financial aid are not new. Last year, many students received their financial aid in the spring semester of this year instead of the fall semester of last year, when the disbursement was supposed to occur.

Adding to the confusion, students often expect the Middle Class Scholarship to be disbursed at the same time as their other aid money. Middle Class Scholarship amounts are often displayed in the university portals with other aid, and California Student Aid Commissions' emails to students.

“Generally it doesn't take this long,” Smith said. “It might take a couple weeks into the school year. But you've at least accepted [it] by that point and they have given you a concrete amount of what you're going to get.”

Smith thought the scholarship would cover his housing, but now he owes a bill for his housing, and he has a hold on his registration until he pays it off.

He said if he doesn’t get the money to pay his housing contract, he will have to work through winter break and register for whatever classes are left, but it would be “par for the course” when trying to get an education.

“I'm no stranger to being broke,” he said. “I'm used to kind of living on the edge of that.”

Rachel Livinal covers higher education for KVPR in Fresno and the Central Valley Journalism Collaborative, a nonprofit newsroom based in Merced.

Data graphics created by Zhaozhou Dai / The Center for Public Integrity & Central Valley Journalism Collaborative